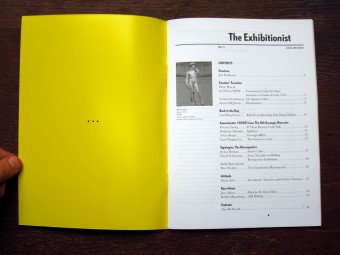

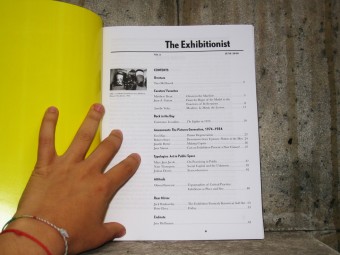

Overture

Jens Hoffmann, Julian Myers-Szupinska, and Liz Glass

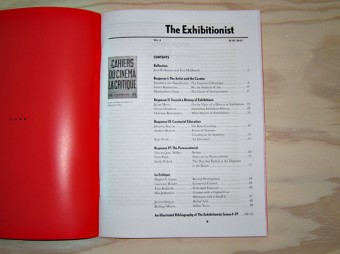

A peculiarity of the current field of curating is an ongoing contestation over the very meaning of “to curate.” As Alice said in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, “The question is whether you can make words mean so many different things.” Humpty Dumpty answers, “The question is which [meaning] is to be master—that’s all.”

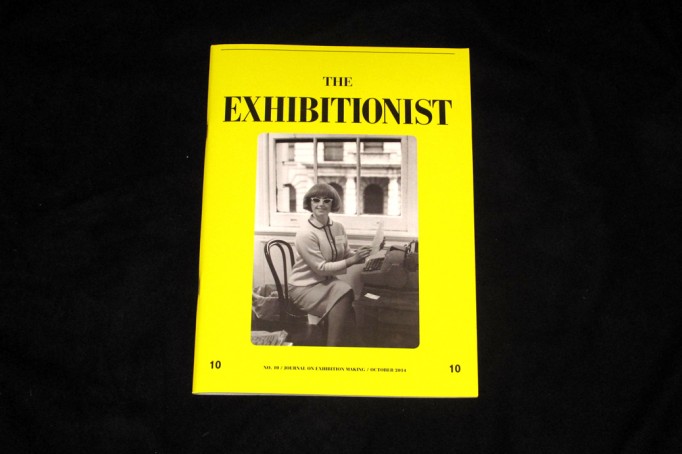

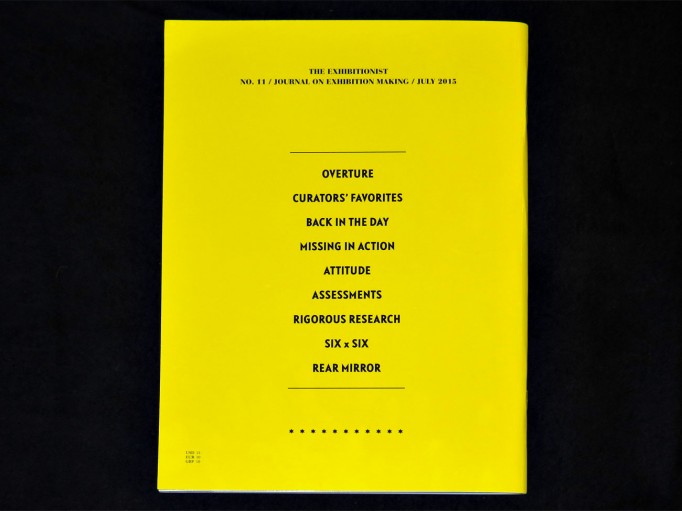

On the cover of this issue is Thomas Ruff’s 1989 portrait of a young Hans Ulrich Obrist. If this fresh-faced guy has done more than most to consolidate the identity of the curator—as a ubiquitous, cosmopolitan character, tirelessly promoting him- or herself, an exhibitionist of the global age—he has also presided over that identity’s confusion and multiplication. Is the curator, as Obrist often describes the role, a catalyst? Or is she, to quote Obrist’s frequent collaborator Suzanne Pagé, a modest commis de l’artiste, an “artist’s clerk”?

Curating has become a global concern, yet many languages still even lack a steady term for it. Meanwhile, in some circles, “curation” has a gained a buzzword-ish currency, signaling taste and discrimination across a dizzying array of cultural activities, from so-called “data curation” to creating playlists and dinner menus. The hope, it seems, is that a renewed connoisseurship might discern value amid the profusions of a global market—separate the wheat from the cultural chaff—even if it means, too, that Kanye West now has as much claim on the term “curator” as Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev or Okwui Enwezor. The more we stretch the word, it seems, the easier it becomes to hijack. It is time for some clarity.

In Attitude, João Ribas meditates on this semantic drift of the word “curating” into marketing, where it is proposed as a cure-all for digital excess and consumer glut. Following John Searle, who warns that the terms we use control the field of meaning, Ribas argues that contemporary curators must battle to retain the understanding that “curating” has held historically in the field of art, beyond connoisseurship and mere selection. He emphasizes in particular the spatial and temporal character of exhibitions, which may still offer the possibility of resisting the behavioral paradigms inflicted by capitalist urbanism and digital technology.

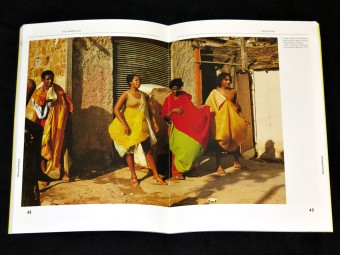

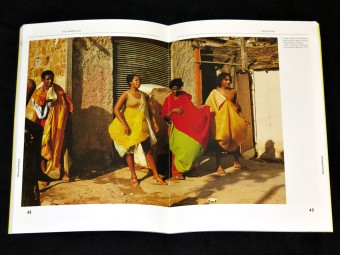

Geopolitical space is a central concern for several essays in this issue. In Back in the Day, Clémentine Deliss contends with the Museum of Modern Art’s notorious 1984 exhibition “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinities of the Tribal and the Modern, which “remains bedeviled by criticisms and emotional refutations that are hard to dissolve.” Comparing that exhibition’s model of “formal affinity” to a recent exhibition by the Senegalese artist and curator El Hadji Sy, she argues for exhibitionary methods that might “effect a remediating affirmation” of ethnographic objects in order to recover something of their “conceptual code.” Missing in Action republishes passages from Rasheed Araeen’s introduction to his 1989 exhibition of British Afro-Asian artists, The Other Story. By assembling the fragments of their collective story, Araeen dismantles the chauvinism of a “master art history” that had excluded non-Western contemporary artists.

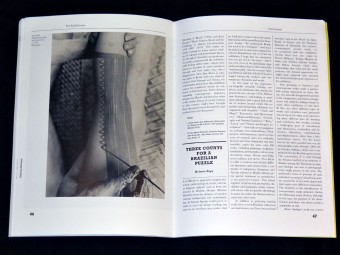

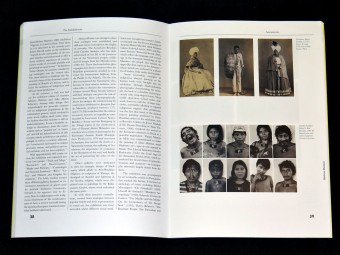

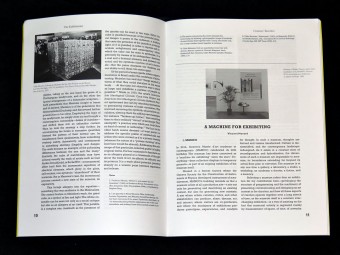

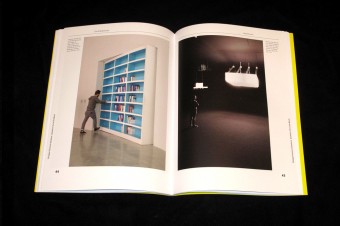

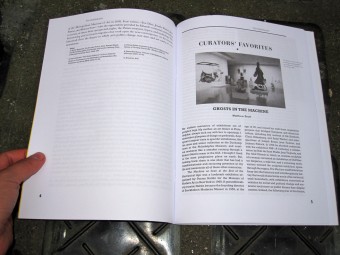

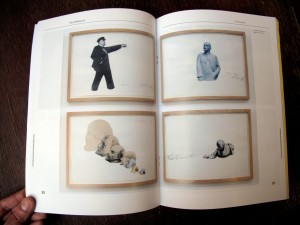

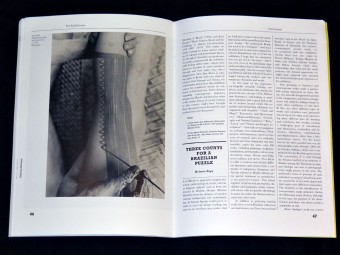

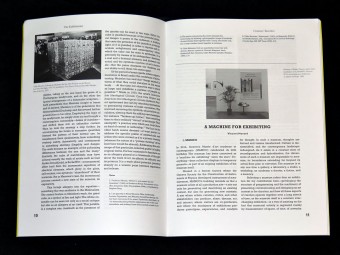

In Assessments, Claire Bishop, Cristina Freire, Tobi Maier, and Octavio Zaya address the exhibition Histórias Mestiças (Mestizo Histories), a trenchant critique of Brazil’s racial democracy curated by Adriano Pedrosa and Lilia Moritz Schwarcz at the Instituto Tomie Ohtake in São Paulo. The writers find consonance around one remarkable installation that juxtaposed photographs of indigenous people by Claudia Andujar, 18th-century watercolors of the “discovery” of Brazil by Joaquim José de Miranda, and drawings from the 1970s by Taniki Manippi-theri, a Yanomami shaman. Says Bishop, “Such an anthropological gaze can diminish the present-ism of contemporary art and allow it to become a method or system of thinking. Would that more curators, in more countries, had the nerve to investigate so unflinchingly cherished national myths.” Curators’ Favorites asks contributors to elaborate on an exhibition that has inspired their thinking. Guy Brett describes a 1979 installation by the Brazilian conceptual artist Cildo Meireles, an allegory aimed at the military dictatorship in power at the time. Natasha Ginwala contends with The One Year Drawing Project, an experimental exchange of artworks across Sri Lanka meditating on the traumas of that nation’s civil war. And Vincent Honoré considers the Musée d’art moderne et contemporain in Geneva, claiming the museum itself as a “constant, ever-changing exhibition.”

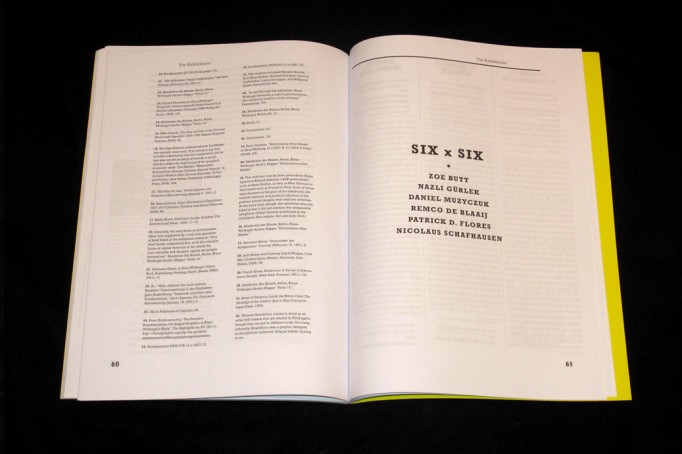

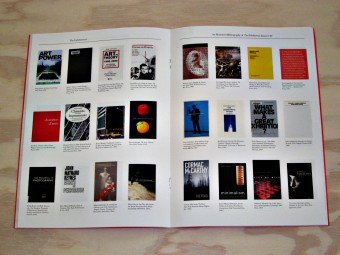

Six x Six challenges curators to name the exhibitions that have mattered most to them. In this issue, Ionit Behar, Astria Suparak, Inti Guerrero, Gianni Jetzer, Sarah Demeuse, and Nikola Dietrich assemble their miniature pantheons. In Rigorous Research, the scholar Vittoria Martini deliberates the little-discussed 1970 Venice Biennale, a turning point for that venerable institution. In the gap opened by a political stalemate, the staff assumed control, and embraced experimentation and research. Research and reflection also connect the two essays in Rear Mirror. Ruba Katrib details the thinking behind her exhibition Puddle, pothole, portal, co-curated with the artist Camille Henrot at SculptureCenter, New York, describing their attempt to capture something of the weird, rambunctious spatiality of early Disney animations. Scott Rothkopf evinces, in turn, the extraordinary spatial and conceptual deliberation behind his recent Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Across this issue, then, the specificity of curatorial labor emerges—the thought needed to build aggregate meaning from disparate things in space. The word “curating” is not infinitely plastic. This, for us, is what it means. We all know how Humpy Dumpty ended up.

€10.00

Buy it