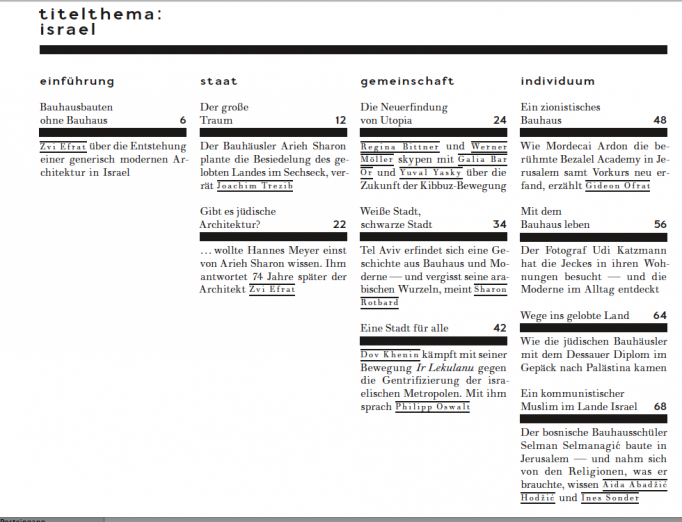

Bauhaus #2: Israel

Issue 2 is all about Israel, reconstructing the migration and transformation of an idea, supported by fomer Bauhaus students who became the most important architects of the emerging state.

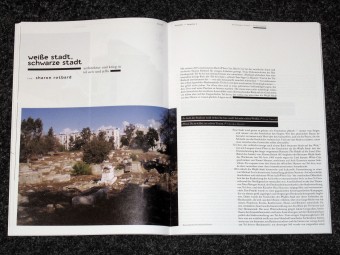

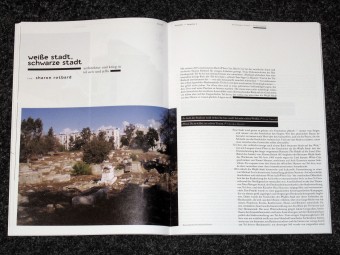

Tel Aviv is more closely associated with the Bauhaus name than any other city outside Germany. But this myth does not stand up to historical inspection. As Sharon Rotbard points out in this magazine, the modern architecture of the ‘White City’ has little to do with the Bauhaus. The myth of the ‘Bauhaus City’ would appear to owe more to the Israelis’ desire to see also, between everything else, the positive in Germany.

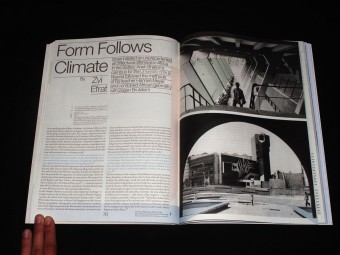

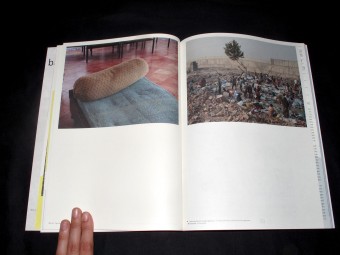

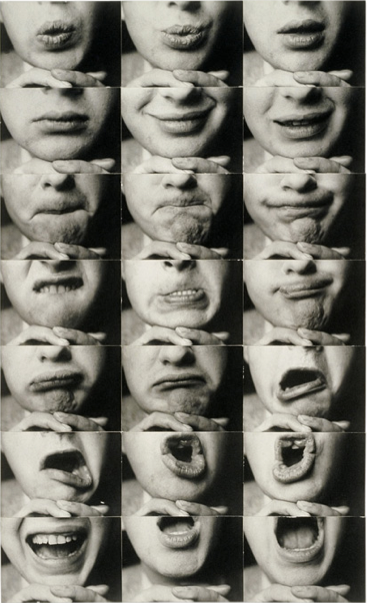

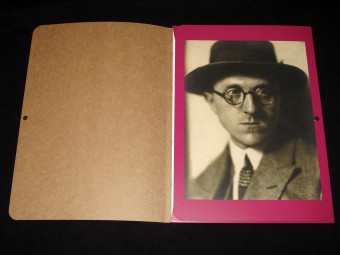

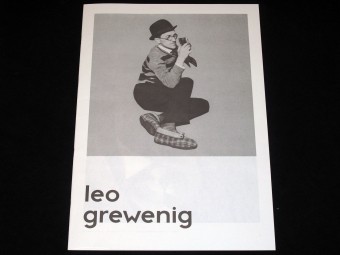

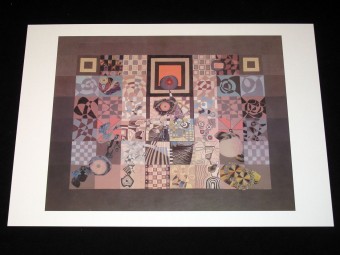

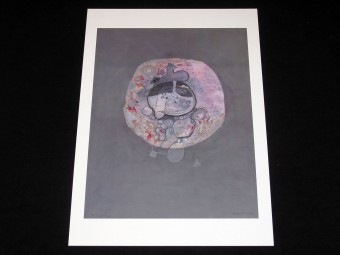

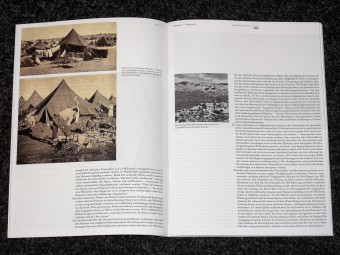

But why, then, a magazine on the Bauhaus and Israel? Freed from the myth, the Bauhaus in Israel may be revealed in an entirely new light. In the homes of German-speaking immigrants, or Jeckes, one can find, for example, material vestiges of migration that refer to European modernism and sometimes even to the Bauhaus itself. Admittedly, far more influence was exerted by the work of over two dozen erstwhile Bauhaus students in Palestine, then later in Israel, including photographers and filmmakers, sculptors and weavers, graphic designers and toy makers and, above all else, the renowned architects and town planners. Having migrated from the Bauhaus Dessau to Palestine or vice versa in the 1930s, they influenced the formation of the new State of Israel in the critical phases before and after its foundation in 1948. This embraced the reformation of the state’s leading art school, the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, by the Weimar Bauhaus student Mordecai Ardon to the master plan for the settlement of the entire state which came about under the direction of Arieh Sharon. But the Bauhaus students Shmuel Mestechkin, Arieh Sharon and Munio Weinraub made the most significant contribution with their work on the design of the kibbutzim from the 1930s to the 1970s. The main exhibition at the Bauhaus Dessau, the opening of which coincides with the publication of this magazine, is dedicated to these built utopian societies. In these fundamentally democratically organised socialist settlements, Jewish migrants from Central and Eastern Europe, together with the Bauhaus students, realised key ideas and ideals of European Modernism. Their common goal was the creation of the ‘Neue Menschen’ (the new people) and the functional organisation of their living environment. In the process, they adhered to a functional understanding of architecture which had, most notably, been informed by the second Bauhaus director Hannes Meyer. These visions were most clearly manifested in the kibbutzim – where they demonstrated their cogency as well as their weaknesses. The nationwide protests in the Israeli cities this past summer showed how topical Meyer’s motto “Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf” (the needs of the people instead of the need for luxury) still is, even if entirely different solutions are being sought today. However, the Jewish resettlement of Palestine in the spirit of modernism also raises questionable aspects: here, the projects of the avant-garde did not impinge on unclaimed dunes, but on the local Arab population. Solutions to the resulting tensions, which were evident at the time have yet to be found.

D 8€

Buy